1. Introduction

Two-dimensional carbon allotrope graphene has been the subject of intensive study since its first discovery due to the unique and exceptional electrical, optical, thermal, mechanical, and chemical properties.1,2) Application fields of graphene include electronics, photonics, optoelectronics,3,4,5) fuel cells,6) energy storage,7) biomedicine,8) etc.2) Regarding the electronic and optoelectronic applications, zero-gap semi-metallic nature of graphene sheets may be a limiting factor since these applications often require semiconductor-like electronic structures of materials. This restriction can be overcome if the sizes of graphene are reduced so that edge structure, either zigzag or armchair, can have controlling effects on its electronic structures, which is manifested in graphene nanoribbons (GNRs).2,9) Furthermore, if the size of graphene is reduced in two directions to yield small platelet-like shape, quantum confinement effect can take place, which is exhibited in graphene nanoflakes (GNFs) or graphene quantum dots (GQDs).2,10) In GNFs, bandgaps are open between the valence band and the conduction band while the band structures notably the bandgaps are dependent upon the shape and size of the dots.10,11) Such controllability of energy band structures of the semiconducting GNFs allows flexibility in their applications to electronics and photonics.

Full exploitation of the properties of GNFs, as contrasted with those of (effectively infinite) graphene sheets, would be possible once their electronic structures are fully understood pertaining to geometric shape, size, edge configurations, functionalization, and so on. Experimental observations can be the best way in that real characteristics are measured. However, diversity of and abundance in the molecular shape, size, and atomic configurations as well as the necessity of scanning tunneling microscopy make the experimental approach costly.12,13,14) Such difficulty may be overcome if computational approaches are taken instead. In this approach, molecular structures (and stability) as well as electronic structures are estimated by density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Based on quantum theories, the DFT calculations provide ample knowledge regarding stability of structures, molecular orbitals, energy band structure, and many physical properties related to the molecular symmetries. Hence, there has been intensive investigation on the structures and properties of GNFs or GQDs by DFT calculations. 15,16,17,18,19,20,21) Despite their advantages, DFT calculations face rising computational costs (both computation time and hardware requirement) as the problem to be solved increase in size (number of atoms building the GNF of concern). In addition, the calculation results are dependent on the choice of calculation levels, pseudopotentials, and computation parameters meaning that there are variations in solutions even for the same GNF systems.

One alternative approach is the semi-empirical method such as tight-binding method (TBM) which is based on the molecular orbital theory. Obtaining the energy eigenvalues and molecular orbitals (wavefunctions) by semi-analytic solution of the matrix form of the simultaneous equations, the TBM allows more convenient handling of large-sized problems where the system under investigations contain even hundreds of carbon atoms. Thus, electronic structures of graphene nanostructures have been investigated for various geometries, sizes, and boundary conditions and for systems containing point defects.10,11,16,2223,24,25,26,27) Meanwhile, each of these works dealt with limited cases whereas there are numerous possibilities of geometries, sizes, and configurations. In addition, most of the works considered GNFs having the sizes in well excess of few nanometers of which the electronic structures converge to GNRs or graphene sheets. Considering that the shape and size effects are more pronounced at smaller systems, it would be informative to investigate the electronic structures of smaller GNFs and related polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) molecules from the perspective of the tunability of electronic structures since the smaller ones will bear more molecule-like nature attributed to the discrete energy states.

In this study, small GNF molecules related to PAHs in terms of molecular structures are considered within the framework of molecular orbital theory. More specifically, simple Hückel approximation or Hückel molecular orbital (HMO) method is employed to calculate the electronic structures, viz. the energy eigenstates, of the GNF molecules having various geometric shapes, sizes, and edge configurations. One objective of this study is to verify that the simple HMO method can be used to screen various types of graphene nanostructures such as GNFs or GQDs by their electronic structures with calculation results comparable to those obtained by more elaborated TBMs, both qualitatively and quantitatively. Additionally, this study is intended to compile the evolution of electronic structures of graphene-related nanostructures as they grow from the fundamental unit of a benzene molecule to the graphene nanostructures having the dimensions at the minimum boundary of GQDs. This will facilitate the molecular design and material selection process in narrowing candidates for specific purposes. Based on such screening results, detailed properties can be investigated experimentally and computationally using more elaborated DFT calculation saving time and cost needed in materials development.

2. Numerical Procedure

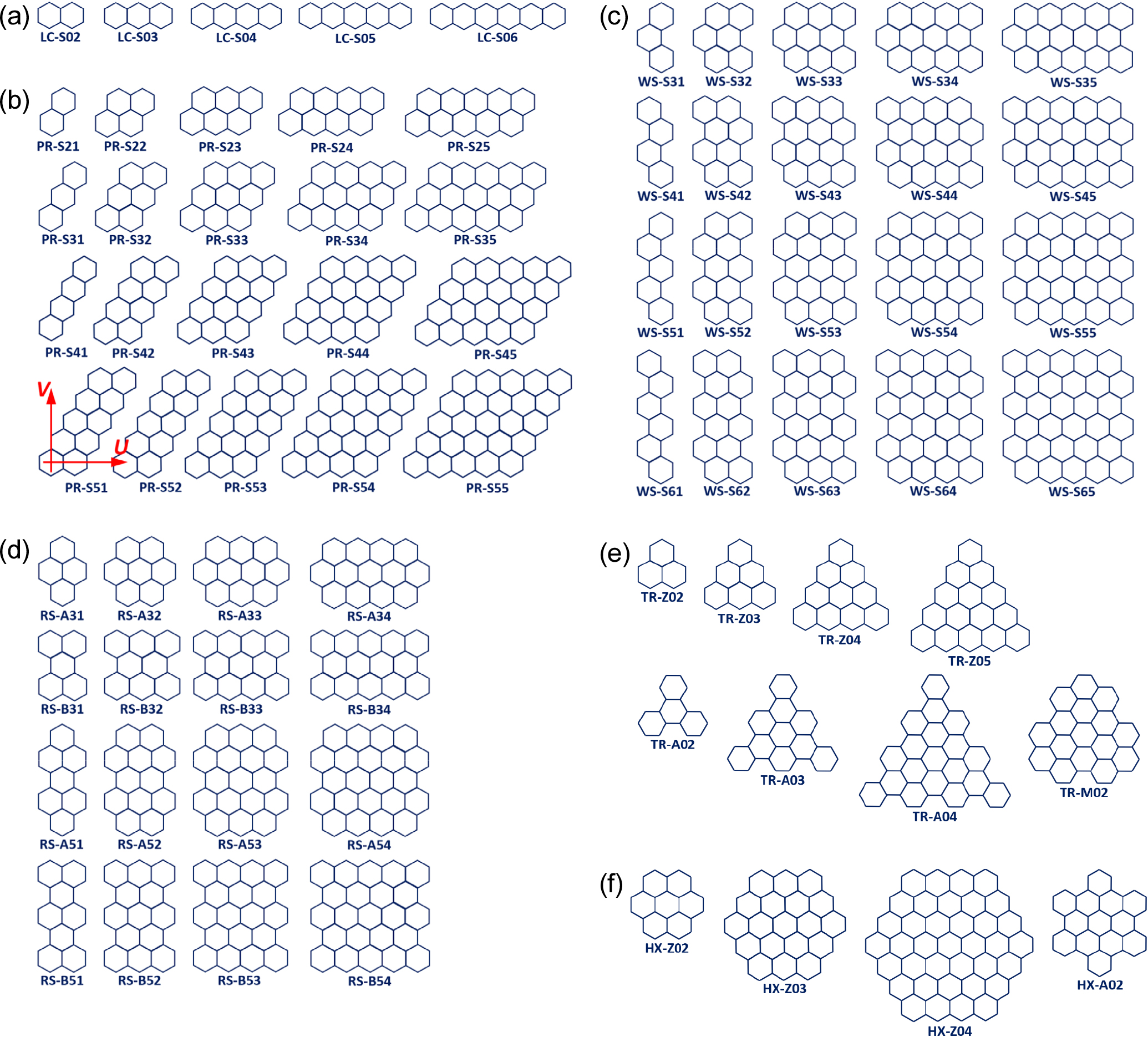

Since graphene shares the hexagonal carbon rings based on the sp2 hybrid orbitals of carbon atoms with the benzene (C6H6) molecule where the π-electrons are delocalized, the model GNF systems can be regarded as PAH molecules constructed by attaching hexagonal sp2 rings to a benzene molecule.28) The GNF systems considered in this study are then constructed on assumption that these PAH molecules conform to various geometric shapes while their maximum sizes slightly exceed 1 nm along their longest directions (either edge or diagonal length). In Fig. 1, these model GNF model systems are grouped by the overall geometric shapes of the flakes. Descriptions of these groups are given as follows with designations revealing their overall shape and geometric features.

i) Group LC: This is the simplest type formed by attaching hexagonal carbon rings to the primary unit of a benzene molecule laterally (along the direction U in Fig. 1) to evolve into a lengthened hydrocarbon molecule assuming a linear chain shape as illustrated in Fig. 1(a). These GNFs have zigzag edges. The molecules included in this group do exist as benzene, naphthalene, anthracene, tetracene, pentacene, etc. The largest LC molecule contains 8 hexagonal rings (34 carbon atoms) reaching the length of 1.96 nm. The designation scheme includes the number of hexagonal carbon rings, NC, along the direction U. For instance, the label LC-S04 stands for a linear chain with NC = 4 sideways.

ii) Group PR: The GNF molecules in this group are constructed by stacking LC chains of various lengths along the vertical direction (direction V in Fig. 1) to take on parallelogram shapes as shown in Fig. 1(b). These molecules are designated further by combining the number of LC chains stacked vertically, m, and the number of hexagonal rings attached laterally, n. Hence, the designation PR-S54 indicates a parallelogram shape GNF molecule formed by 5 rows (m = 5) and 4 slanted columns (n = 4) of LC chains. The GNF molecules in this group have zigzag edges. PAHs such as naphthalene (PR-S21), pyrene (PR-S22), anthanthrene (PR-S23), etc. are included in this group.

iii) Group WS: The molecules in this group are formed by stacking various LC molecules along the vertical direction in a staggered arrangement as shown in Fig. 1(c). Consequently, the GNF molecules in this group have wavy armchair type vertical edges while their top and base edges have zigzag configuration. These molecules are also designated by the combination of m and n like those in the Group PR. The molecules having one column (n = 1) include phenanthrene, chrysene, picene, and fulminene.

iv) Group RS: GNF molecules may have overall rectangular shape by stacking vertically two LC chains of the length difference by one hexagonal ring in alternating manner along the vertical direction while maintaining mirror symmetry with respect to both the lateral and the vertical axes with their origins at the geometric centers of the molecules. The GNF molecules in this group, having zigzag top and base edges and armchair vertical edges, are further classified into two subgroups as shown in Fig. 1(d). Those with odd-numbered C-C dimers along the vertical edges are designated as subgroup A (RS-A53 for instance) and with even-numbered dimers along the vertical edges as subgroup B (RS-B-32 for example).

v) Group TR: Benzene rings can be assembled in such a manner as to make the GNF molecules have triangular shapes as shown in Fig. 1(e). The smallest in this group is phenalene (C13H9) in which the number of zigzag edge units, NE, equals 2. Attachment of hexagonal rings to maintain the same triangular symmetry yields triangulene (NE = 3), [4]triangulene (NE = 4), and so on. Such subgroup is denoted as TR-Z followed by NE. Hence the label TR-Z03 denotes triangulene taking an example. Triangular GNF can have armchair edges, too. The smallest molecule in this subgroup is triphenylene (C18H12) which has two dimers and one bay along each edge. Molecules can be enlarged by increasing the number of dimers, ND, one by one with the number of bays along each edge equal to ND - 1. The molecules in this subgroup are denoted with the label TR-A followed by ND. So, TR-A02 indicates triphenylene. An additional type considered for the electron structure calculation is the one having three zigzag corners, which is labeled as TR-M22 (M for mixed edge and 22 for two dimers and two zigzag units along each edge).

vi) Group HX: The last group to be considered has hexagonal symmetry. The GNFs in this group can have diverse terminations including zigzag, armchair, gulf, and cove edges. In this study, however, only those having zigzag edges are considered as shown in Fig. 1(f). The molecules in this group have the designation of HX-Z followed by NE. For example, the label HX-Z02 indicates coronene (C24H12). For comparison purposes, one GNF with armchair edges is included in the calculation which has two dimers (ND = 2) along each edge. This molecule is designated as HX-A02.

Once the model systems are constructed and grouped in a manner described above and in Fig. 1, their electronic structures are estimated using the HMO method. The electronic structure in this context is the energy states (also called eigenstates) of the GNF molecules corresponding to the molecular orbitals formed by the linear combination of the pz orbital of each carbon atom that do not participate in the sp2 hybridization. These eigenstates or energy eigenvalues can be found by solving the matrix equation of the form

In this matrix equation, the matrix H, called the π-electron Hamiltonian matrix, is constructed from the atomic Coulomb integrals α of the carbon atoms themselves and the resonance integral β between the nearest two neighboring carbon atoms. The matrix E is a diagonal matrix consisting of the energy eigenvalues of the molecular wavefunctions which can be constructed using the coefficients in the matrix C obtained as the eigenvectors corresponding the energy eigenvalues. The matrix S is the overlap matrix which is equal to the unit matrix I as a basic assumption of the HMO method. Setting the matrix S equal to the unit matrix I may be an oversimplification, but this facilitates the solution of Eq. (1) with relative ease and yields solutions comparable both quantitatively and qualitatively to those obtained by more elaborated TBMs as will be shown later in the results section.

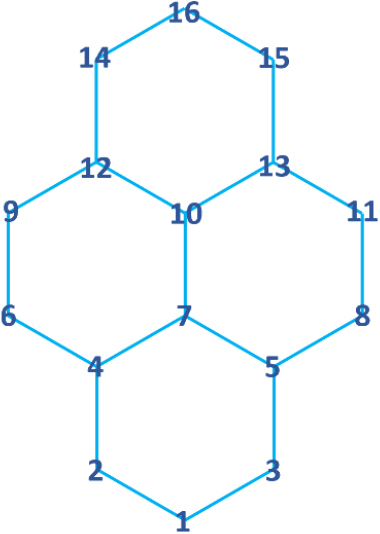

The procedure of solving Eq. (1) is essentially the diagonalization of the H matrix. One example of the H matrix is shown here for a pyrene (C16H10, RS-A31 in Fig. 1). Since this molecule consists of 16 carbon atoms, the molecular orbitals originate from the linear combinations of the pz orbitals of the 16 π-electrons. The corresponding H matrix is then constructed, in accordance with the sequence of numbering the carbon atoms shown in Fig. 2, as the following 16 × 16 matrix.

Diagonalization of this matrix is a process of solving the equation

of which the solution procedure is well documented in textbooks of quantum chemistry, for example one by Levine.29) The H matrix is invariant in that the positions of the off-diagonal non-zero components (β’s) are dependent on the numbering sequence of the carbon atoms in the molecule, which can be chosen arbitrarily, whereas the results of the diagonalization, viz. the energy eigenvalues, are always the same. To solve Eq. (3), the H matrix can be expressed in the form

where, vA is the vertex adjacency matrix. Using this expression, Eq. (1) can be rewritten as

If α is taken as the reference state energy, i.e., α = 0, and β is used as the unit of energy, Eq. (5) is simplified as

which is in fact a non-linear equation of nth degree for unknown energy eigenvalues Eii (i = 1, …, N where N is the number of the carbon atoms as well as of the π-electrons in the molecule). By this approach, the energy eigenvalues for the molecular orbitals can be first calculated and the difference in the energies of the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) EHOMO and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) ELUMO, ΔEH-L (= ELUMO - EHOMO), is obtained by considering the configurations of the π-electrons in the molecular energy level (or eigenstate) diagrams.

3. Results and Discussion

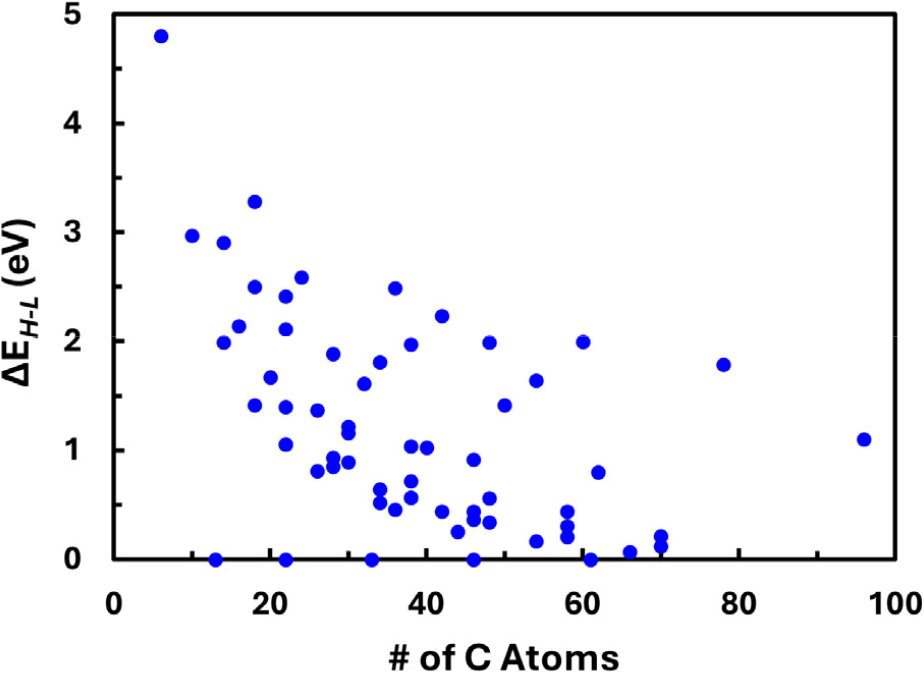

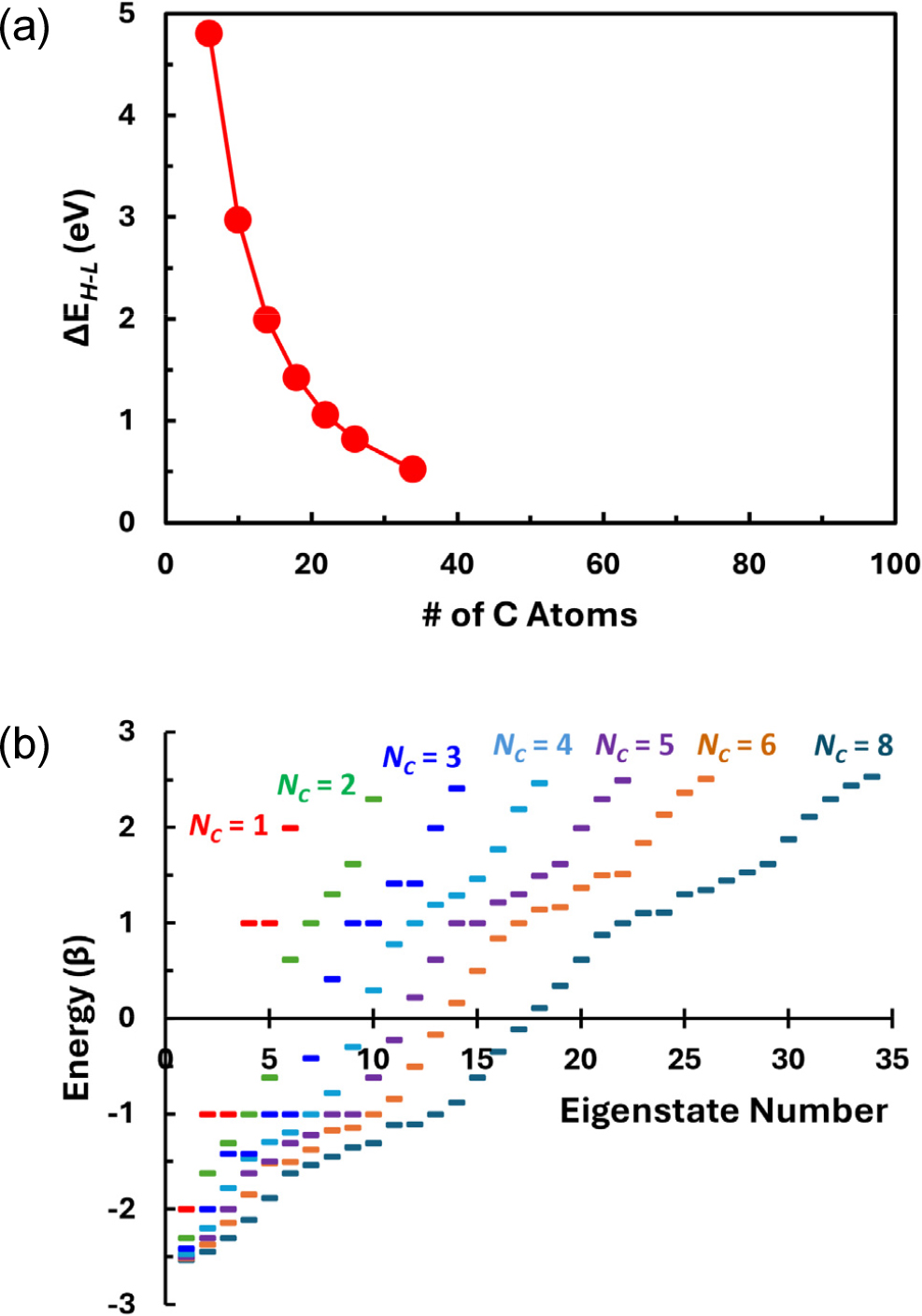

It is at first glance expected that increase in the size of the GNF molecules result in the decreasing energy gaps between the HOMO and the LUMO, HOMO-LUMO gaps or ΔEH-L. Thus, changes in ΔEH-L with increasing number of carbon atoms in the GNF molecules, viz. growing size of the molecules, are plotted first and the results shown in Fig. 3. In this plot, the energy unit β was taken to be 2.40 eV for graphite for convenience, although the exact value may depend on the C-C bond length of each molecule and therefore resulting variations in the overlap integral S.30,31,32,33) It should be mentioned that these ΔEH-L values are used only for the comparison purpose in this study and shall not be taken as absolute values since the overlap integral matrix S in Eq. (1) is set equal to the unit matrix I in the framework of the HMO method. It is noticed that ΔEH-L indeed decreases as the GNFs become larger. It is 4.80 eV for benzene, the fundamental hexagonal ring unit of graphitic materials, and decreases to 0.068 eV for the GNF of the label RS-B54 which has rectangular shape and contains 66 carbon atoms. On the other hand, for a GNF with 96 carbon atoms having hexagonal shape (label HZ-Z04), ΔEH-L is as high as 1.10 eV although this GNF contains more carbon atoms and is therefore larger in size. Further, ΔEH-L = 0 regardless of size for some GNFs which have triangular shape with zigzag edges. It may be said from Fig. 3 that smaller ΔEH-L is expected with larger size of GNFs, but it can also be said that this correlation is not strong, since there is wide scatter in the data points. This implies that the HMO in this study may have properly reproduced the results originating from more than the size effect. Hence, the electronic structures of the GNFs are to be considered by the geometry groups as listed in Fig. 1 hereinafter.

In the case the GNFs in the Group LC, Fig. 4(a) shows that the changes in ΔEH-L with increasing chain length by the addition of hexagonal rings lengthwise follows the 1/Ln (n = 1.06) dependence where L is the chain length in nm, which is close to the experimental observations and the predictions by TBM and DFT for various GNF systems reported in other works.1,12,13,18,24,34) When the chain length reaches 1.96 nm (LC-S08 in Fig. 1 containing 34 carbon atoms), ΔEH-L = 0.218β (or 0.522 eV for β = 2.40 eV). This 1/L dependence of ΔEH-L also predicts that ΔEH-L would approach a value comparable to the thermal energy of electrons at room temperature (about 0.026 eV) only when the chain is built with about 1,000 hexagonal rings.

Fig. 4.

(a) Changes in ΔEH-L with varying size of the linear chain type GNFs (Group LC). Each data point from left to right indicates increasing length by attachment of one additional hexagonal carbon ring. (b) Comparison of the energy level (eigenstate) configurations for the linear chain GNF molecules with various lengths.

Concerning the electron structure, the molecular energy eigenstates are shown in Fig. 4(b) for all the GNFs under consideration. The energy state configurations for LC-S05 (NC = 5) and LC-S08 (NC = 8) are consistent with those obtained by the nearest-neighbor tight-binding model reported elsewhere.25) The evolution of the electronic structure with increasing size as shown in this figure suggests that initially discrete energy states with wide energy gaps between them will become quasi-continuous with increasing length of the chain. Degeneracies at (for odd-numbered NC’s) or near (for large even-numbered NC’s) the energy of E = α ± β imply that there would be relatively higher density of states (DOS) near E = α ± β. This is also consistent with the predictions by TBM for the same LC type GNFs elsewhere.25)

In this energy state diagram, it is seen that the energy gap between the LUMO and the next higher (first excited) level is relatively large despite the decreasing ΔEH-L with increasing molecule size. In the case of the LC-S08 GNF, this difference is 0.572 eV (equivalent to 0.238β), comparable to the ΔEH-L of 0.522 eV. Additional upper energy levels are spaced with similar energy differences until the energy eigenvalue becomes α - β. Therefore, it is expected that any excitation of electron energy state from the HOMO to LUMO will be followed by another discrete excitation to the upper energy states if any external energy is provided by photons, heating, or electric fields, etc. The discrete energy states with relatively large spacings indicate that the GNF would show optoelectronic or electrical properties resembling quantum dots in the length scale regime of about 1 nm. However, lengthening molecular chain will eventually lead to the configuration of closely spaced energy states that allow these LC type GNFs to have almost metallic characteristics.

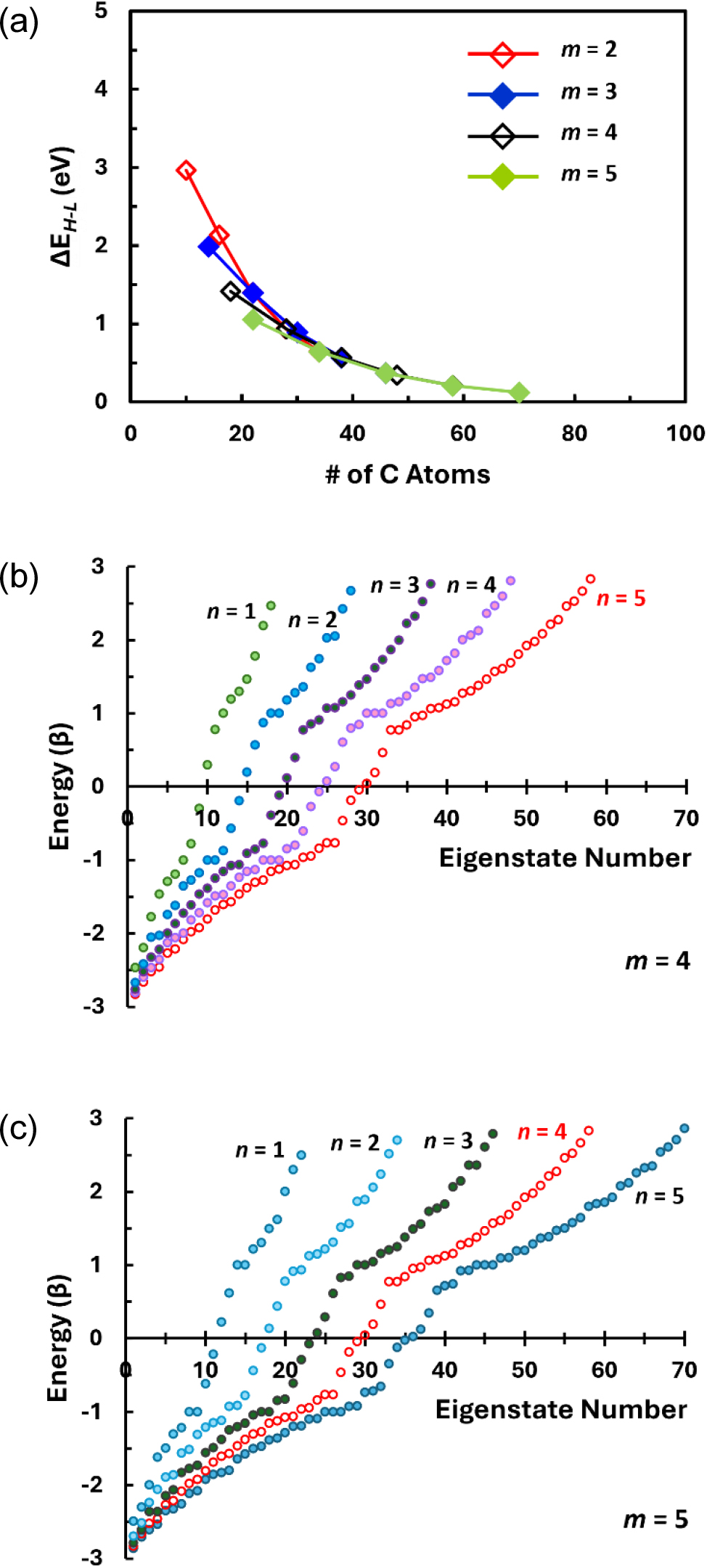

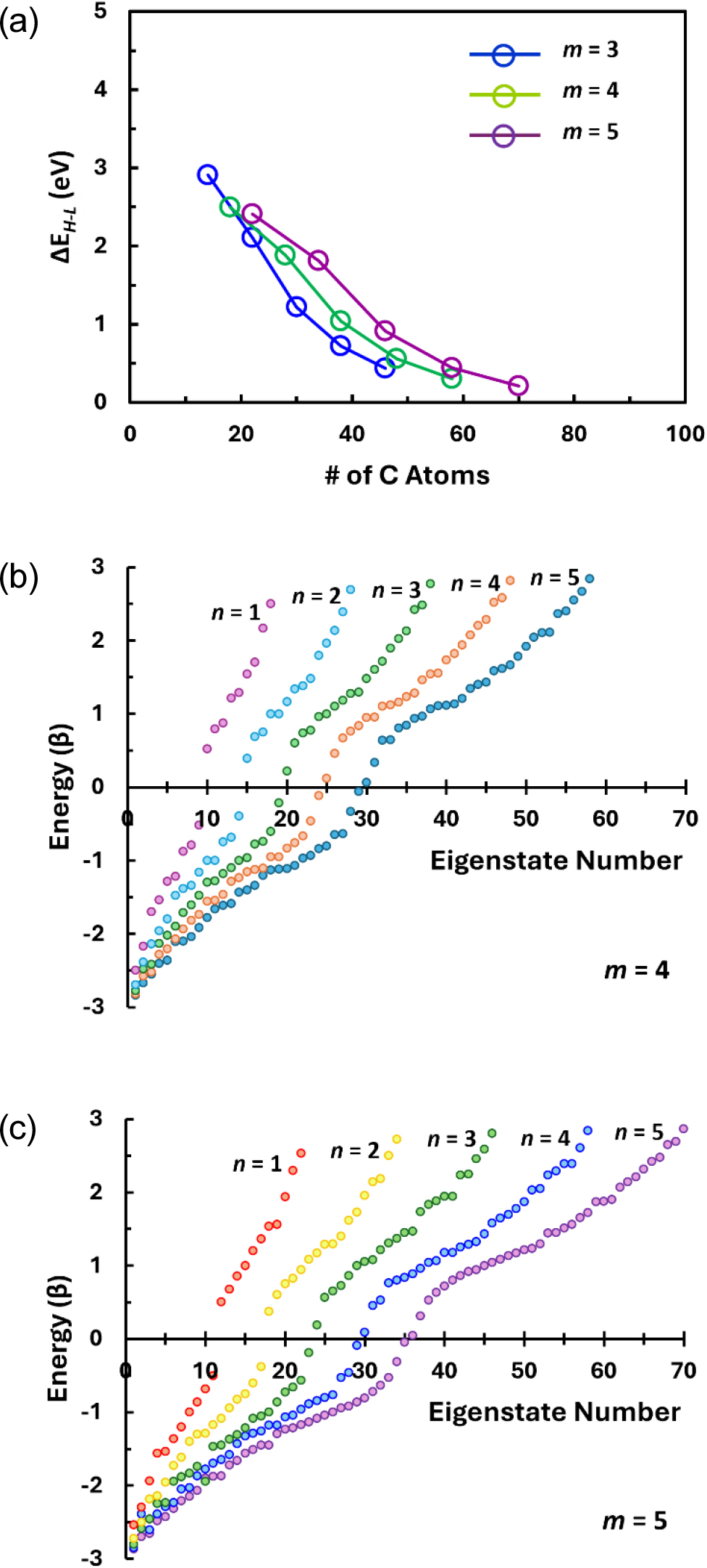

While the GNFs in the Group LC are regarded as one-dimensional linear molecules, two-dimensional molecules will be more common types. One possible geometry is a parallelogram (Group PR). For these GNFs, changes in ΔEH-L with the increasing number of carbon molecules are plotted in Fig. 5(a) against the varying number of LC layers, m, stacked along the direction V. It is seen that for any given m, ΔEH-L decreases with increasing number of carbon atoms along the lateral direction (increasing n), reflecting the size dependence of ΔEH-L. In addition, the GNFs having more rows of hexagonal rings along the vertical direction (larger m) tends to have smaller ΔEH-L, for n = 1 and 2, but this effect becomes less pronounced with increase in the overall size of the GNFs, as revealed in the converging ΔEH-L curves with higher number of carbon atoms. This indicates that the electron structure of the GNFs having parallelogram geometry would evolve rapidly into that of an effectively infinite graphene sheet. Indeed, for the GNF that consists of five rows and five columns, i.e., (m, n) = (5, 5), which consist of 70 carbon atoms and has the edge length of 1.23 nm, it is predicted that ΔEH-L = 0.120 eV. This relatively small energy gap may endow this GNF with almost metallic electrical and optical characteristics. However, the electron energy structure shown in Fig. 5(b, c) for the GNFs with m = 4 and 5, respectively, suggests that this would be possible only when the electrons are excited to higher energy levels around E = α - β, since energy states are relatively closely spaced with narrow gaps only above this level meaning higher DOS above E = α - β. On the other hand, there are substantially fewer energy states between the LUMO and the molecular orbital corresponding to E = α - β although some population of eigen states are expected near the LUMO and HOMO with decreasing ΔEH-L as the GNF becomes larger in size. Such a trend of relatively higher DOS near and above E = α ± β and of sparce DOS between E = α + β and E = α - β seems to be general characteristics of small sized GNFs of any shape. 11,22,24,25,27,35,36) Consequently, electrical and optical characteristics of the parallelogram type GNFs will exhibit partially semiconductor-like and partially metal-like characteristics when their sizes are relatively small.

When the linear chains of carbon rings are stacked along the vertical direction with a staggered arrangement, the resulting GNFs [those in the Group WS in Fig. 1(c)] are expected to exhibit different electron structures. Comparison of the changes in ΔEH-L with increasing GNF size in Fig. 6(a) for this GNF geometry with those in Fig. 5(a) for the parallelogram geometry (PR) shows that the GNFs having staggered configuration would have larger ΔEH-L than the parallelogram counterparts for the same combination of (m, n). The difference between the PR and WS geometry is the existence of armchair edge(s) in the latter configuration. This implies that the presence of armchair edges may provide the GNFs with conditions for a larger energy gap between HOMO and LUMO whereas the zigzag edges favor the smaller one. This is a general tendency predicted for and observed in GNRs with small widths.13,22,25,37) However, presence of the armchair edges does not seem to have noticeable effect on the distribution of the energy states of small GNFs in this study as seen in Fig. 6(b, c), which appear somewhat similar to Fig. 5(b, c). In this respect, it is inferred that the GNFs formed by stacking linear chain of hexagonal carbon rings would show similar optoelectronic properties irrespective of their overall geometric shapes.

Fig. 6.

(a) Changes in ΔEH-L with varying size of the GNFs having staggered arrangement of linear chains of hexagonal carbon rings (Group WS). (b) and (c) Comparison of the energy level (eigenstate) configurations for the staggered arrangements of hexagonal carbon rings formed by stacking 4 and 5 LC layers, respectively.

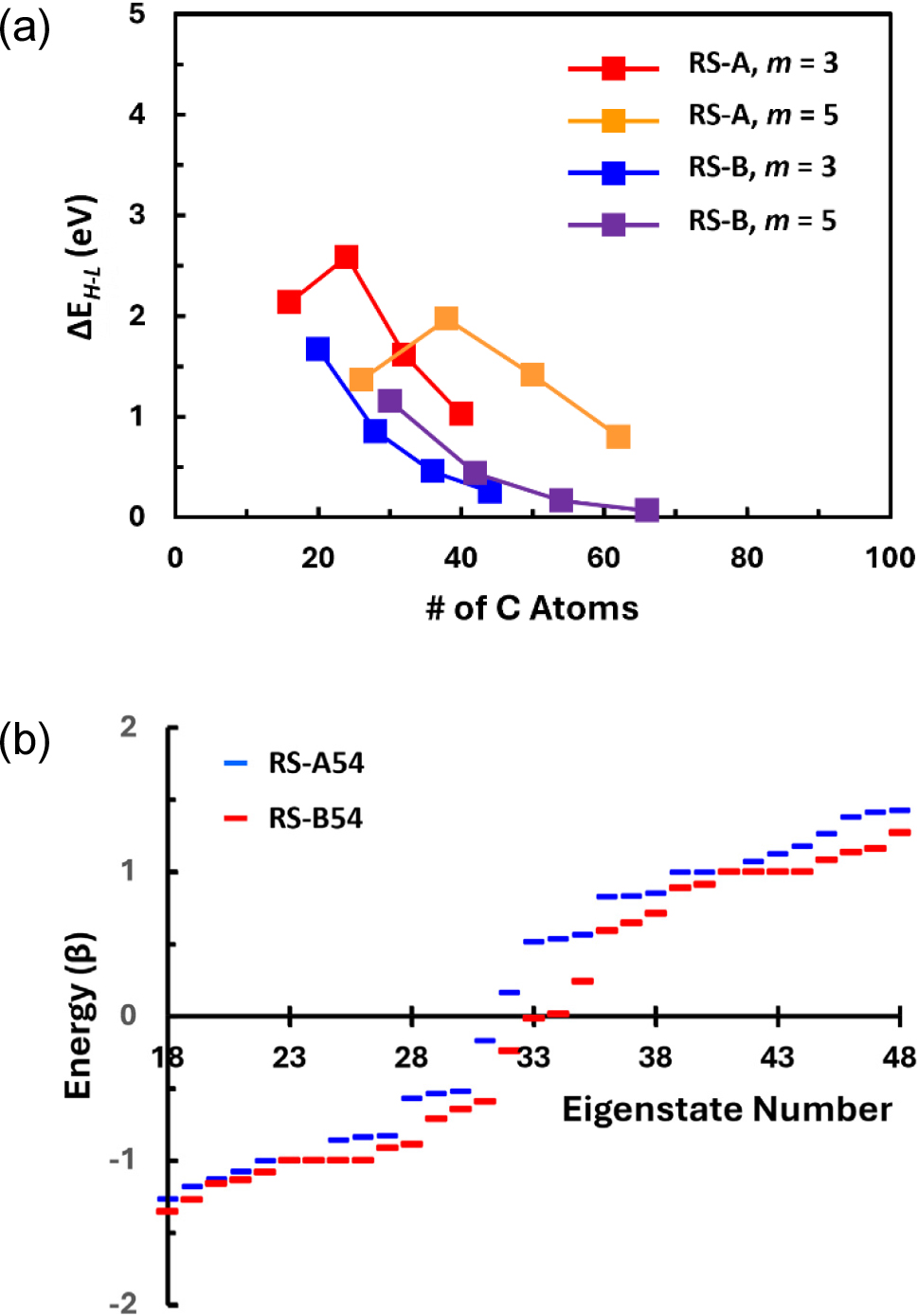

The next case to be considered is the GNFs formed by the stacking two linear chains of length difference by one hexagonal ring alternately along the vertical direction, which results in the overall geometric shapes of rectangles [labeled as the Group RS in Fig. 1(d)]. This group being classified into two subgroups, one with odd-numbered C-C dimers along the vertical edges (subgroup RS-A) and the other with even-numbered dimers along the vertical edges (subgroup RS-B), there are two distinct trends in the changes in ΔEH-L with increasing GNF size as shown in Fig. 7(a). It is first noticed that the ΔEH-L of the GNFs in the subgroup RS-A initially increase as the molecule structure changes from pyrene to coronene (m = 3) and from peropyrene to circumbiphenyl (m = 5) by lateral addition of phenanthrene (m = 3) and picene (m = 5) columns, respectively. This is then followed by decreasing ΔEH-L with increasing GNF sizes by further lateral addition of phenanthrene and picene columns. Contrary to this, ΔEH-L for the RS-B type GNFs decrease gradually with increasing size. Further, much larger ΔEH-L’s are expected of the GNFs in the subgroup RS-A than the subgroup RS-B despite the latter has one more bay along the parallel vertical armchair edges. In addition, within the same subgroup, the GNFs with smaller number of vertical stackings, m, shows smaller ΔEH-L when they have similar number of carbon atoms. These results suggest that the relative portion of the zigzag edges has major contribution to ΔEH-L and it can surpass the effect of the number of carbon atoms (size effect). The smallest ΔEH-L expected among the considered configurations is 0.068 eV for RS-B54 which consists of 66 carbon atoms.

As to the electron structure, the energy level configurations near the HOMO and the LUMO of the GNFs RS-A54 and RS-B54, which consist of 62 and 66 carbon atoms respectively, are compared in Fig. 7(b). For these two GNFs, ΔEH-L’s are predicted to be 0.334β (= 0.801 eV) and 0.028 β (= 0.068 eV), respectively. These gaps alone may indicate that the subgroup RS-A would have more semiconductor-like characteristics than the subgroup RS-B. However, it should be noted that the energy gap between the LUMO and the first excited level above the LUMO is much larger than the ΔEH-L’s in both the cases. Further, the energy levels would be relatively closely spaced only from the three-fold (RS-A) and four-fold (RS-B) degenerate levels at E = α - β. This can be regarded as increased densities of states (DOS) at higher energy levels well above LUMO’s.11) Considering large value of the resonance integral β, about 2.4 eV for infinite graphene sheet and perhaps even larger for smaller finite graphene-related molecules, both types of the GNF may exhibit somewhat semiconductor-like electrical conduction behavior if there are some ways of exciting the electrons from lower levels around E = α + β, where another increased DOS is expected, to the upper levels around E = α - β. Otherwise, the optoelectronic behavior of these GNFs would resemble that of quantum dots, which is more likely considering their length scales barely exceeding 1 nm, since the first few excite levels from LUMO are rather widely spaced.

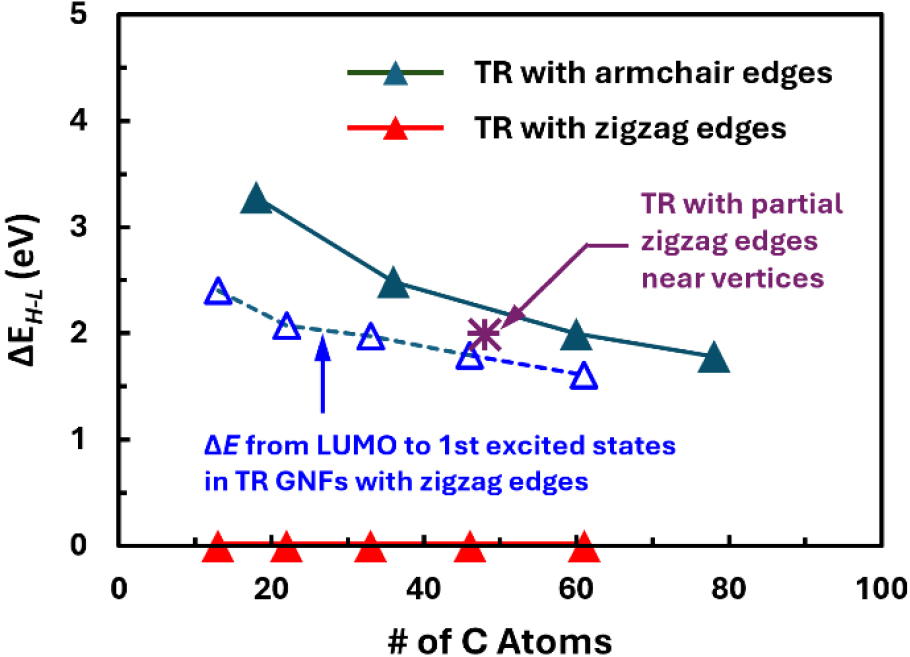

Now, the symmetry effect is considered by examining the electron structures of the triangular [Group TR in Fig. 1(e)] and the hexagonal [Group HX in Fig. 1(f)] GNFs. Depending on the arrangements of carbon atoms, triangular GNFs may have three zigzag edges [subgroup TR-Z in Fig. 1(e)] or armchair edges [subgroup TR-A in Fig. 1(f)]. Such a difference in the edge configurations makes a marked difference in the electron energy level structure as shown in Fig. 8. One noticeable feature in this figure is that the HOMO-LUMO gaps vanish (ΔEH-L = 0) for the zigzag-edged triangular GNFs regardless of the size, which is not the case for the other (non-triangular) GNFs considered so far.25,26,35) Since the HOMO and the LUMO overlap at the same energy level, the zero-energy state would have at least two-fold degeneracy. This may imply that the triangular GNFs have metallic characteristics even at the smallest possible size with NE = 2. However, the first excited states above the LUMO are separated by large energy gaps ranging from 1.61 eV (TR-Z05 with NE = 5) to 2.4 eV (TR-Z02 with NE = 2), which is consistent with previous predictions by TBM elsewhere.35) Depending on the number of degeneracies at the zero-energy state, such large energy gaps between these two closest energy states may result in the electrical and optical properties substantially different from truly metallic large-sized GNFs.

On the other hand, triangular GNFs with armchair edges are characterized by large ΔEH-L gap. For instance, it is predicted that the GNF of TR-A04 configuration will have the ΔEH-L as large as 2.00 eV even though it is constructed with 60 carbon atoms leading to the edge length of 1.56 nm. This ΔEH-L is substantially larger than those of other GNFs having comparable number of carbon atoms (and comparable dimensions) considered so far. This implies that the armchair edge effect on the electron structure is maximized in this type of GNF and that the triangular GNFs with all armchair edges will show semiconductor-like behavior like small-width GNRs having armchair edges. Interestingly, if the carbon atoms are assembled in such a way to add zigzag corners around all three vertices [that with the label TR-M22 in Fig. 1(e)], somewhat smaller ΔEH-L is expected as separately marked in Fig. 8. However, this small decrease in ΔEH-L would indicate that the introduction of zigzag vertices does not alleviate the effect of armchair edges noticeably.

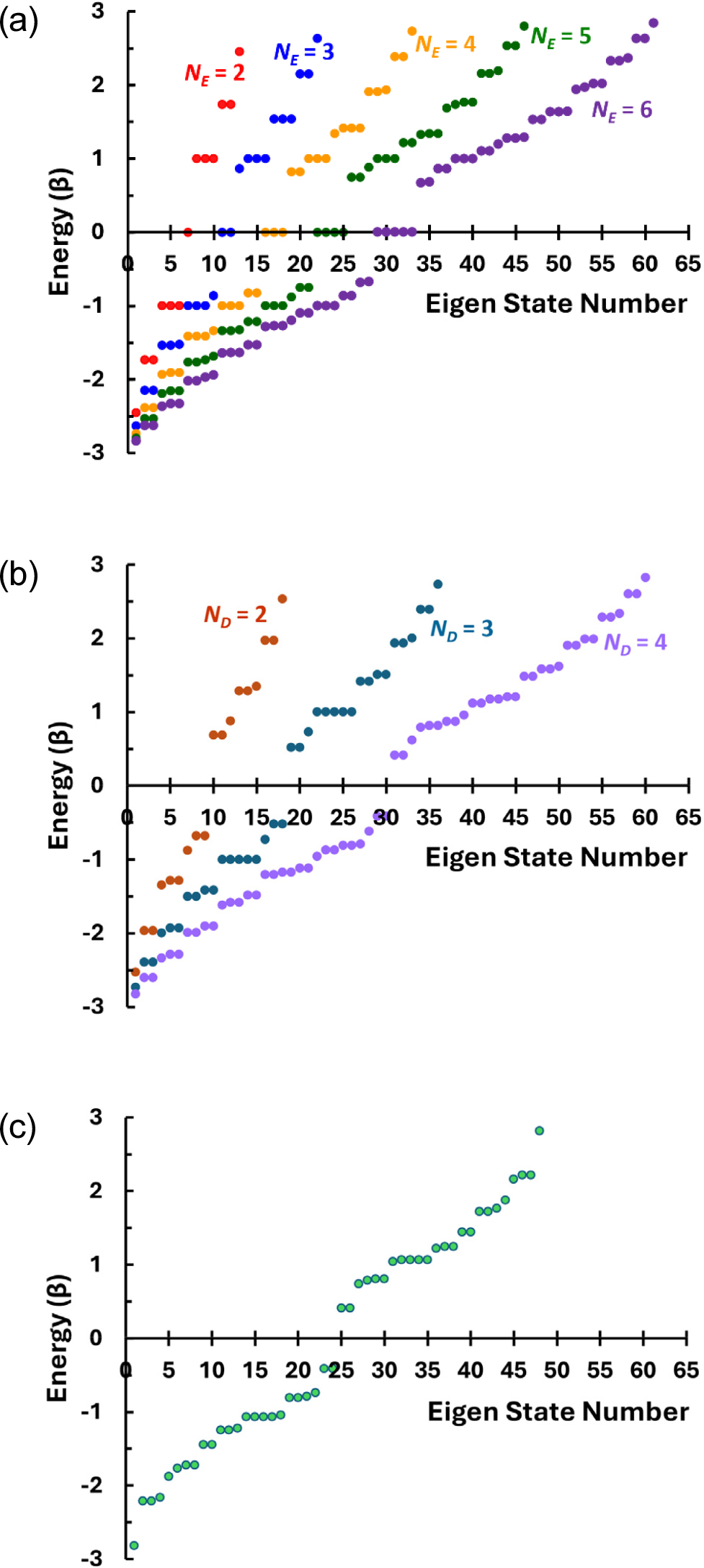

Detailed electronic structures are now considered using the energy level diagram shown in Fig. 9 for the expected electrical, optical, and magnetic properties. In Fig. 9(a), energy levels are compared for the GNFs with zigzag edges. It is first seen that the degeneracy of the zero-energy state follows the ‘NE - 1 rule’ as predicted by TBM in previous works.25) Hence, degenerated zero-energy state is possible only when NE ≥ 3, and larger GNFs will have more degenerated zero-energy state. In Fig. 9(a), it can also be seen that there are triply degenerated states at E = α ± β. This degeneracy does not increase with increasing size of the GNF. Instead, additional states appear in its proximity resulting in some spread of energy states near this energy state of E = α ± β, which is responsible for the decreasing energy gap between the LUMO and the first excited state from it with growing GNF sizes in Fig. 8. These features in the distribution of the energy states are consistent with those predicted by more elaborated tight-binding model reported elsewhere, demonstrating the validity of the HMO method in this study despite its simplicity.

Further, when the GNF is small, the energy states are discrete with large energy differences. In this case, the optical and electrical properties of the GNFs will resemble those of quantum dots. As its size increases, more energy states are added gradually near the initially discrete (and degenerated) states. Consequently, the distributions of the energy states are more like mini bands, accompanied by increasing density of states especially near the energy state of E = α ± β. This is an indication of the evolution of the electronic structure into metallic type. Even at small length scales as considered in this study, as the zero-energy states are degenerated, only half the molecular orbitals will be occupied by the π-electrons having the same spins in accordance with the Hund’s maximum multiplicity rule. Therefore, somewhat metal-like electronic properties may be expected even for small-sized triangular GNFs having zigzag edges. Further, unlike the other cases where the HOMO is fully occupied with paired spins, the GNFs having zigzag edges will show at least paramagnetism or even ferromagnetism as predicted elsewhere.38)

When the triangular GNFs have armchair edges along all their sides, as seen in Fig. 9(b), their energy states develop in different ways. First, there is no zero-energy state, and this yields large HOMO-LUMO gaps whilst they decrease gradually with increasing size of the GNFs. In addition, the manyfold degeneracies at E = α ± β following the NE - 1 rule does not exist for the GNFs having even-numbered dimer units along the edge. Only in the GNF with TR-A03 configuration having three dimer units along the edges (ND = 3) show 5-fold degeneracy at this energy state. Meanwhile, as in the case of the zigzag GNFs, increase in size result in somewhat continuous distribution of the energy states except the HOMO-LUMO gap indicating the evolution of the electronic structures from quantum-dot-like one to semiconductor-like one with relatively higher density of states near E = α ± β.11,25) Similar energy state structure is expected for the GNF having mixed edges of armchair sides with zigzag vertices, suggesting that the armchair effect can be mitigated only marginally by the introduction of partial zigzag corners.

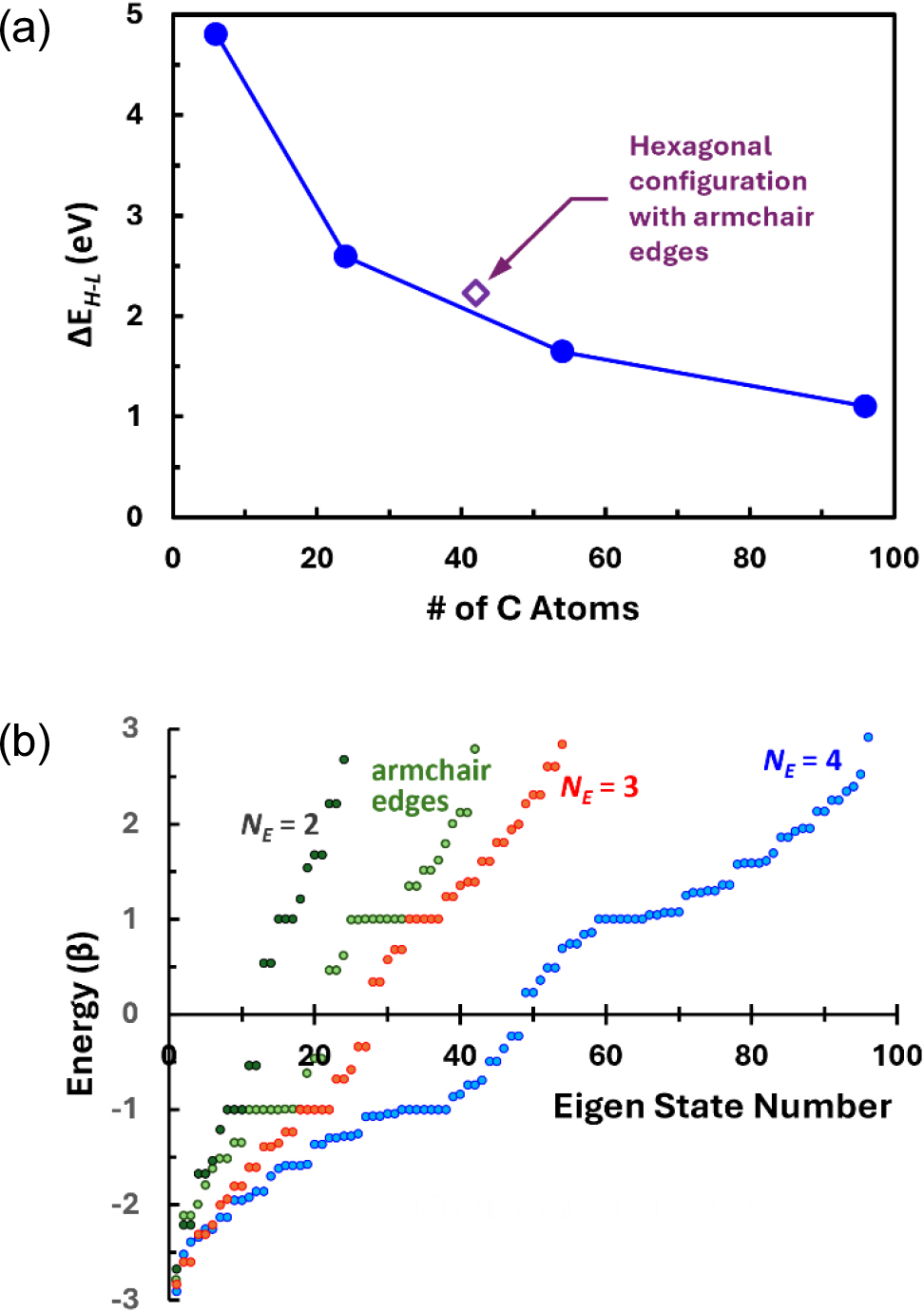

Another peculiarity is expected once the GNFs have hexagonal symmetry. In this case, as shown in Fig. 10(a), the HOMO-LUMO gaps, ΔEH-L, are larger than other types of GNFs of comparable size considered in this study even though the hexagonal GNFs have zigzag edges all along their sides. Even when the size of the GNF reaches 1.72 nm across by having four hexagonal carbon rings along each edge [HX-Z04 in Fig. 1(f)] to contain 96 carbon atoms, the HOMO-LUMO gap, ΔEH-L, would still be 1.10 eV. This situation seems not to be significantly affected by the introduction of the armchair edges.31) The ΔEH-L of 2.23 eV separately shown for a hexagonal GNF constructed with 42 carbon atoms, which possesses armchair edges with one bay along all its six sides [HX-A02 in Fig. 1(f)], is not substantially larger than ΔEH-L = 1.64 eV for a GNF with zigzag edges having 54 atoms (HX-Z03), considering the size differences between the two.

In addition to the large HOMO-LUMO gaps, another characteristic of the hexagonal GNFs is their highly degenerated energy states at E = α ± β as shown in Fig. 10(b). When the GNFs have zigzag edges, these degeneracies are odd-numbered.25) As the number of carbon rings, NE, along one edge increases from 2 to 4, the degeneracies increase from 3 to 7. For a sufficiently large GNF (NE = 4, HX-Z04), some more degenerated energy levels exist close to the energy level corresponding to E = α ± β, implying highest density of state at and near E = α ± β. In this case, additional energy states are expected between the HOMO and the LUMO, suggesting that the increasing size of the zigzag-edged hexagonal GNFs would eventually show metal-like electronic structure, including possible zero-energy state, revealing the effect of edge states in the zigzag edges as predicted elsewhere.10,24,25,27)

While the detailed electronic structures of the GNFs considered so far are affected by the shape and symmetry, edge configurations, and size, the general trends can be summarized as: i) the HOMO-LUMO gaps decrease with increasing size of the GNFs or number of carbon atoms included in the GNFs and ii) the zigzag-edged GNFs have narrower HOMO-LUMO gaps compared with the armchair-edged ones having comparable sizes. Decreasing HOMO-LUMO gap can be understood in the context of the molecular orbital theory which predicts that numerous energy levels must be configured between the ground state corresponding to the fully bonding orbital and the top-most excited state corresponding to the fully antibonding orbital of which the energy difference is finite. In the case of the two-dimensional GNF (effectively PAH) molecules considered in this study, the ground state converges to α + 3β and the top-most excited state to α - 3β with increasing number of carbon atoms yielding this energy width of 6β. Hence, the gaps between the molecular energy levels would decrease resembling the formation of energy bands in solids.39) Eventually, when the GNFs are sufficiently large, the energy levels will evolve into energy band and the HOMO-LUMO gap will vanish as in the case of infinite graphene sheets. The smaller HOMO-LUMO gaps of the zigzag-edged GNFs as compared to those of the armchair-edges counterparts can be attributed to the presence of the nonbonding localized edges states at the Fermi level, i.e., the localization of the wavefunction on the edge sites, which stems from the topology of the π-electron networks, i.e., edge termination by only one of the sublattices. On the other hand, being terminated by paired sublattices, no such localized state exists at the armchair edges.13,14,22,40,41) While such statements are concerned with the GNRs where the distance between two parallel edges are relatively larger than GNFs, similar rules seem to be applicable to the GNFs considered in this study following the calculation results. In this case, the edge effect would be more pronounced due to the smaller size of the nanostructures and closer distances between the edges. Since the study of edge states for the zigzag-edged GNFs are limited to the case of triangular and hexagonal GNFs,10,24,25) more detailed study based on the wavefunction calculations would be needed to better understand the edges effect for GNFs with various shapes and symmetries. This is left as the future work.

4. Conclusion

Application of the HMO method to the investigation of the electronic structure of GNFs at the length scale of about 1 nm and below demonstrates that this method yields the results comparable to those obtained from more rigorous TBM qualitatively and quantitatively despite its simplified assumptions verifying its effectiveness. Investigation of the electronic structures of the GNFs in accordance with their overall geometric shape, size, edge configurations, and symmetry suggests that at small length scales below or near 1 nm as considered herein, their optoelectronic characteristics may exhibit variations dependent upon the geometric shape (symmetry) and edge configurations, which play more significant roles in determining the electronic structures than their sizes. It is suggested that the method employed in this study can be taken as an initial screening stage of tailoring and designing characteristics of graphene nanostructures having other different geometries and containing vacancies and 5-7-7-5 defects, which is then followed by more detailed methods such as density DFT calculations.